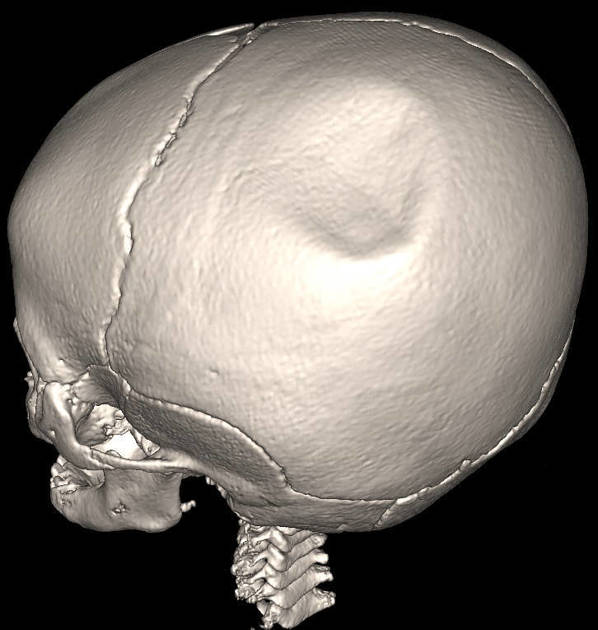

Brain damage, particularly CTE, has widely been discussed in the past decades as a negative consequence of football. Beyond action on the field, a growing body of research reveals that this damage may be exasperated by the equipment worn by players to prevent harm. Research links heavier football helmets to increased brain injury risk in young players.

Virginia Tech’s Helmet Lab found that children, whose neck muscles are weaker and heads proportionally larger than adults’, are especially vulnerable – sustaining concussions at approximately 60g of head acceleration, compared to roughly 100g for college athletes. This knowledge has resulted in a drive of both equipment reforms and legislative action for youth football across the United States. Led by the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment, new StandardND005 regulations were finalized in July 2025. Youth football helmets must be a maximum of no more than 3.5 pounds, effective September 1, 2027.

States are also not waiting. In West Virginia, Senate Bill 657, the Cohen Craddock Student Athlete Safety Act, named for a 13-year-old who died August 24, 2024, from a football-related brain injury, advanced through the Senate Education Committee on February 12, 2026. The bill would allow schools to adopt protective soft-shell helmet covers during practices. At the federal level, Senator Durbin (IL) introduced S.2889 on September 18, 2025, conditioning federal education funding on state-level concussion safety protocols. (Beyond this initial reading, no further action appears to have been taken.)