“Dinner today is going to be a big steak and, for dessert, a huge bowl of ice cream.”

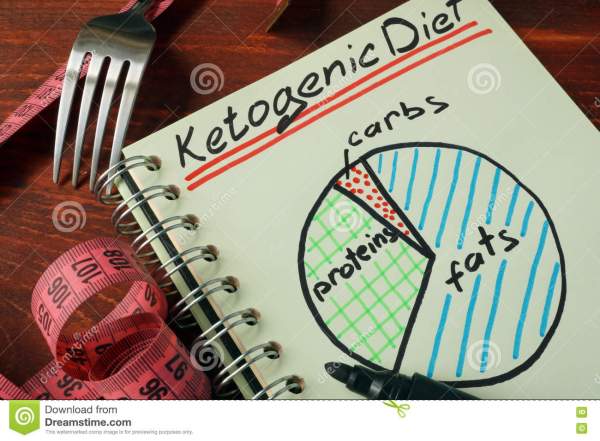

The above meal may seem like a recipe for weight gain, but it is also a meal in tune with the ketogenic diet. A diet trend for about a decade, the ketogenic diet (KD) seeks to, “mimic biochemical changes associated with starvation,” states the NIH. The basic idea of this diet is to limit the carbohydrates one consumes, and eat a diet of 80 – 90% fat, in order to put the body into a starvation state. This extreme limitation of foods that are turned into glucose means that the metabolic source used for energy production must be changed by the body, so that it goes into a ketonic state.

People with chronic diseases/conditions have said that KD promotes their overall health, reduces their symptoms, slows their diseases progression and even may be a treatment for it. In a 2008 study, titled Diet, Ketones and Neurotrauma, scientists noted, “This altered dietary approach may have tremendous therapeutic potential for both the pediatric and adult head injured populations.” Since that time, over 20 studies have been done that show that KD both helps you lose weight and improves your health. This year, in fact, the NIH reviewed past studies and performed new animal studies that showed, “The KD is an effective treatment for TBI recovery in rats and shows potential in humans… [however] the human trials did not establish much evidence with respect to the KD as a treatment for TBI.” Again, the NIH concluded that further research is needed.

What has been determined is that the ketogenic diet is beneficial for some people who have particular neurological disorders – specifically children with epilepsy. As far back as 1921, the KD diet was used as a treatment for epilepsy in children with positive results. Since the diet is very strict it may be the last option, but it is still an option, especially for epilepsy – a disorder that can be caused or exasperated by traumatic brain injury. Additionally, it seems that the ketogenic diet may be beneficial for treatment of diabetes, as it lowers blood sugar. Diabetes has been shown both to be a possible consequence of brain injury or a possible cause of brain injury. Even if a brain injury is not involved, the symptoms of hyperglycemia, the identifying mark of diabetes and other disorders, mimic those of TBI. In fact, “Among the secondary complications, hyperglycemia (both peak glucose and persistent hyperglycemia) in TBI patients is one of the most common and correlates with the severity of the injury and clinical outcome.” (However, the Cleveland Clinic notes that, “Eating a lot of sugar can lead to tooth decay, but it does not cause diabetes.”)

In reality, most people will embark on a diet at some point in their lives. Even with all this inconsistent evidence, the ketogenic diet is still on trend, largely because of celebrity endorsements by such people as Kim and Kourtney Kardashian, Halle Berry, Gwyneth Paltrow and LeBron James. Be aware though, that whenever you intake a greater amount of calories than your body needs, you will gain weight. And even if you intake the correct number of calories, but not the right nutrients, your body will suffer. This is even more true for those with severe and/or ongoing disorders/diseases, such as brain injury.